17 Famous Norman Rockwell Paintings & Why They Still Hold Value in 2026

Norman Rockwell paintings are often remembered because of the story they told for the time. For decades, his work shaped how Americans saw themselves, not through grand historical scenes, but through everyday moments that people could relate to.

Beneath the polished surfaces and carefully staged scenes, though, there was always more going on. The ideas Rockwell explored told a bigger story about America, and their meaning still resonates decades later.

The Norman Rockwell paintings below trace the evolution of his career. Together, they show why he remains one of the most famous painters and influential American artists of the 20th century, not just for what he depicted, but for how closely his work followed the country’s changing sense of itself.

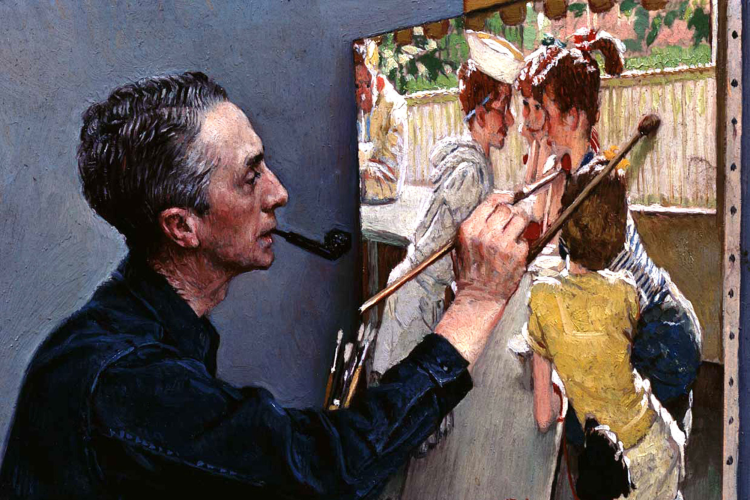

Feature image: Self-Portrait of Norman Rockwell Painting the Soda-Jerk (via James Vaughan; CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Jump to Section

Who Was Norman Rockwell?

Norman Rockwell was an American illustrator whose work came to define how much of the 20th century saw itself. Born in New York City in 1894, he showed artistic promise early on and at just 14 years old, he quit high school and enrolled at the Chase Art School. He continued his studies at the National Academy of Design, followed by the prestigious Art Students League of New York, where he developed his technical skills under the guidance of renowned artists of the time.

At just 18, Rockwell landed his first professional assignment illustrating Carl H. Claudy's children's book Tell Me Why: Stories about Mother Nature. And by his early 20s, he was already working professionally, landing what would become a career-defining relationship with The Saturday Evening Post.

From there, he quickly gained popularity and was thrust into the national spotlight. His illustrations were characterized by meticulous and realistic attention to detail with a warm subject matter. At just 22 years old, in 1916, Rockwell sold his first cover to The Saturday Evening Post, a publication that became synonymous with his art.

Over the next five decades, Rockwell produced more than 300 magazine covers, most depicting ordinary people caught in small but telling moments. His scenes of family life, childhood, work and community became visual shorthand for American identity, especially during periods of upheaval like the Great Depression and World War II.

During World War II, Rockwell's Four Freedoms series, inspired by Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1941 speech, became emblematic of American resilience and values. These paintings toured the country, raising millions for war bonds and cementing Rockwell's reputation as a national treasure. They were also reproduced in thousands of posters.

Later in his career though, Rockwell’s focus shifted. He began addressing more overt social and political themes, including civil rights, poverty and war. These works challenged the long-held idea that Rockwell was merely sentimental, revealing an artist deeply engaged with the moral tensions of his time.

By the time of his death in 1978, Rockwell had left behind more than 4,000 original works, with a legacy that extended beyond magazine covers; his body of work became a visual archive of 20th-century America. He received numerous accolades, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1977.

This is not to say that Norman Rockwell’s paintings are without cultural commentary. While Norman Rockwell paintings were frequently dismissed by critics in his earlier years for being “too soft,” he gained more legitimacy as an artist from the early 1940s to the late 1960s, when he began to paint about pressing social justice issues.

Rockwell published his autobiography in collaboration with his son Thomas, called My Adventures as an Illustrator, in 1960.

The Most Famous Norman Rockwell Paintings

1. The Peace Corps (JFK's Bold Legacy) (1966)

(via Norman Rockwell Art Collection Trust)

Created five years after President John F. Kennedy established the Peace Corps, Rockwell’s The Peace Corps captures a moment of American idealism shaped by collective purpose over individual heroism.

Kennedy appears in profile at the center of the painting, leading a diverse group of individuals arranged closely behind him. But instead of being shown above the group like he usually would, Rockwell integrates the president into the scene, suggesting leadership is rooted in participation rather than authority.

Painted during Rockwell’s later career, after his move toward more politically engaged work, The Peace Corps reflects a moment when American identity was tied to cooperation, optimism and moral leadership — ideals that remain both resonant and contested today.

2. The Problem We All Live With (1963)

(via singulart)

The Problem We All Live With is perhaps one of Norman Rockwell’s most confronting works. It features Ruby Bridges, who, at only six years old, was the first black child to attend a formerly all-white school in the American South.

When the painting was published in Look magazine in 1964, it marked a turning point in Rockwell’s career. Long associated with sentimental scenes of American life, he used this work to confront racism directly, aligning his art with the Civil Rights Movement and asking viewers to reckon with injustice as it unfolded.

Ruby is shown in a crisp white dress, carrying her schoolbooks, escorted by four U.S. marshals whose faces are deliberately cropped out of the frame. By removing their identities, Rockwell forces the viewer to look at Ruby — her small stature, her composure and her quiet resolve. The anonymity of the marshals points to the imbalance of power and responsibility placed on a child.

That hostility is communicated subtly but unmistakably. Racial slurs are scrawled on the wall behind her and a smashed tomato lies on the ground, remnants of violence that never enter the frame directly but remain present.

Despite this, Ruby continues forward, self-possessed and dignified, embodying resilience in the face of hatred.

3. New Kids in the Neighborhood (1967)

(via Norman Rockwell Museum Collection)

New Kids in the Neighborhood is one of the Norman Rockwell paintings that demanded attention. It highlights a quieter but no less charged moment in America’s desegregation story.

Rockwell depicts two newly arrived Black children in a previously all-white neighborhood with three white children across from them, paused mid-play, studying the newcomers with a mix of curiosity and uncertainty. Even the family dog seems unsure how to react. No adults appear in the scene, leaving the emotional weight to rest entirely on the children’s body language and expressions.

It is Rockwell’s restraint that gives this painting its power. There is no visible violence or hostility, only hesitation and unfamiliarity. The children mirror one another in posture and scale, suggesting equality, while their distance reflects the social divide.

4. Murder in Mississippi (Southern Justice) (1965)

(via Norman Rockwell Museum Custom Prints)

Murder in Mississippi is one of Norman Rockwell’s darkest and most unflinching works. It stands as a bold acknowledgment of violence embedded in American history and a reminder that bearing witness can itself be an act of resistance.

Inspired by the real-life murders of civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner during Freedom Summer in 1964, the painting abandons Rockwell's usual style entirely in favor of moral urgency.

The three figures in the foreground, who are shown in the moments after violence has already taken place, are surrounded by the ominous shadows of the murderers on the ground in the background. While Rockwell never depicts the act itself, the aftermath is unmistakable.

5. The Right to Know (1968)

(via Norman Rockwell Family Trust)

Painted during a period of growing public distrust in government, this work centers on the idea that democracy depends on transparency. The Right to Know is one of the most renowned Norman Rockwell paintings. It was painted towards the end of Rockwell’s career during a time of growing opposition to the war in Vietnam. He used composition and gaze to ask a pointed question: who holds power, and who deserves answers?

In the painting, a group of citizens is shown standing in a courtroom, facing forward as if awaiting testimony or judgment. It positions the viewer from the perspective of the witness stand, placing responsibility directly on the audience. The figures vary in age and background, reinforcing the idea that access to truth is not reserved for elites but owed to everyone. Rockwell actually includes himself in this painting, pipe in hand, implicating the artist in the demand for accountability.

Like most Norman Rockwell paintings, this was produced using oil on canvas, one of the most popular paint mediums both then and now. If you're on a quest to understand oil painting for beginners, Norman Rockwell paintings provide a masterclass on the medium, ending the debate on acrylic versus oil paint.

Rockwell used light to enhance his realism, similar to that of the Impressionist painting tradition; he directs your eye and builds emotion through small details. If you're looking for things to paint, start with the details, like Rockwell.

6. War News (1943-44)

(via Norman Rockwell Museum Collection)

Painted during World War II, this piece captures the emotional weight of conflict as it filtered into American life. But instead of depicting soldiers or battlefields though, Rockwell makes you look at the moment when news arrives back home.

He shows four characters, a Western Union boy, a clerk, a deliveryman and a server gather around a radio in a diner to listen to a report. Deliberately leaving the content of the news ambiguous, allowing viewers to project their own fears and memories into the scene.

Unlike many of Rockwell’s wartime images, War News never appeared as a Saturday Evening Post cover. Its emotional restraint and unresolved tension may have made it too unsettling for mass reassurance.

7. Hey Fellers, Come On In! (1920)

This is one of the lighter Norman Rockwell paintings, which leans into the uncomplicated joy of boyhood. There’s no lesson being delivered and no larger moral at play — just a fleeting moment of childhood freedom shortly after World War I.

Two boys are swimming carelessly in a body of water. One bobs his head above water in the background while the other steals the viewer’s attention, waving as if to invite you to jump in for a swim. The loose composition and relaxed body language reinforce the sense that time has slowed, if only briefly.

Above national identity or social change, Rockwell looks at something more intimate — the memory of carefree summer days and the ease of belonging that comes with youth.

8. Christmas Trio (1923)

(via Norman Rockwell Art Collection Trust)

Set against a winter backdrop, this painting captures a small, intimate moment of celebration. Three figures, two men and one child, are bundled up in winter clothing, singing a Christmas carol together.

The trio is centered on the canvas with fine details outlining their expressions and movements, while the background remains still, almost lightly sketched. Created shortly after WWI during a period of renewed optimism, the scene reflects a collective craving for tradition and human connection.

9. Freedom from Want (1943)

(via Norman Rockwell Museum)

Freedom from Want is the first in this series of Norman Rockwell paintings: The Four Freedoms series. It's a domestic scene that becomes a statement about security, abundance and shared ritual. In the painting, a family is shown gathering around the dinner table to share Thanksgiving food.

Rockwell frames the figures closely, drawing attention to faces, hands and glances, overshadowing the food and the turkey. The composition centers on togetherness, not indulgence. Painted during World War II, the scene reflects an ideal many Americans hoped to preserve — stability at home.

Freedom from Want isn't just about sentimentality; it's also about assurance. It presents prosperity not as excess, but as the simple ability to gather, eat and feel safe.

10. Freedom of Speech (1943)

(via Norman Rockwell Museum Custom Prints)

Where Freedom from Want focuses on private life, this work shifts to a public scene. A blue-collar man is shown in simple clothes, standing up to speak at a town hall meeting. Although part of the working class, he stands tall and confident even though he is surrounded by men of a higher class.

The speaker isn’t heroic or polished, just steady and unflinching. Everyone else listens. The composition reinforces the idea that participation, not status, gives democracy its weight.

Painted during World War II, the image argues that freedom isn’t abstract. It exists in regular rooms, shaped by people willing to stand up and be heard.

11. Freedom of Worship (1943)

(via WikiArt)

The third installment of the series looks at religious belief. A group of individuals is shown, each occupied in prayer or worship, each shown worshiping in their own way, based on their own private religious beliefs. We only see the characters' faces and hands, but they’re portrayed in acute detail.

With no setting specified and no single faith centred on, Rockwell strips away context so the act itself carries the meaning. The differences are visible, but so is the shared posture of reverence.

12. Freedom from Fear (1943)

The final of the Norman Rockwell paintings in this series shifts inward, away from public ideals and back to the private space of home, like the first instance in the series. Parents tuck their children into bed, shielding them from the anxieties of a world at war. The scene feels familiar, but Rockwell layers it with unease.

That unease lives in the details. The father holds a newspaper bearing headlines about bombings and destruction, a reminder of the fear adults carry even as they try to preserve calm for their children.

The juxtaposition between the sleeping kids and the weight of the news underscores the fragility of safety during wartime. The result is one of the most emotionally restrained works in this series of Norman Rockwell paintings, capturing the desire to protect innocence in the face of uncertainty.

13. Rosie the Riveter (1943)

(via Norman Rockwell Museum Custom Prints)

We all know of Rosie the Riveter as a strong symbol of the roles women took on during World War II, especially the notorious image "We Can Do It!" by J. Howard Miller. But Rockwell uses this image to reframe wartime strength. In this Rockwell scene, Rosie is positioned in a powerful stance as if she were a monument, with her foot stomping on a copy of Adolf Hitler's infamous and corrupt book.

Her muscular arms, factory uniform and steady gaze challenge traditional gender roles without spectacle. Rosie’s foot rests on a copy of Mein Kampf, grounding the image in the global stakes of the war, while her posture recalls classical depictions of heroic figures. The result is not propaganda in the abstract, but a portrait of resolve shaped by labor, responsibility and purpose.

14. Growth of a Leader (1964)

(via Wikipedia; Fair Use)

This painting looks at leadership not as a title, but as something shaped over time. Rockwell presents a simple before-and-after: a Boy Scout and the man he becomes, shown side by side, linked by posture, clothing and shared stillness.

The uniform changes, the body grows and responsibility settles in. It’s less about authority and more about continuity — how values are passed down and how character forms gradually, long before anyone is officially “in charge.”

Unlike other Norman Rockwell paintings that appeared on magazine covers, this Norman Rockwell painting appeared in the 1966 Brown & Bigelow Boy Scout calendar.

15. Triple Self-Portrait (1960)

(via Norman Rockwell Museum Custom Prints)

This work turns inward, offering perhaps one of Rockwell’s most self-aware moments. Instead of depicting American life from the outside, he places himself squarely in the frame — and then complicates it through painting technique.

Rockwell portrays himself in this painting, his own self portrait while looking into a mirror, creating a layered loop of observation and interpretation. The finished canvas differs from the man we see at work, subtly reminding the viewer that every image is a construction. What looks straightforward is, in fact, carefully edited.

Playful but thoughtful, it’s less about vanity and more about authorship — who controls the story, and how much of the artist is visible in the final image.

The trippy painting idea and use of composition, with its inherent introspection, make it one of the most abstract painting ideas in the canon of Norman Rockwell paintings — a far cry from the typical moments he normally captured.

16. Breaking Home Ties (1954)

(via Totally History)

Breaking Home Ties looks at a moment of transition; nothing dramatic happens, but everything is about to change. A son sits beside his father on the side of an old car, neither character looking the other in the eye.

The young man wears a crisp white suit and keeps a briefcase by his foot, ready to begin a new adventure. The father hunches over in his work clothes, holding a hat in his hand. Rockwell leaves the emotional weight in the space between them, letting posture and silence do the work.

17. Saying Grace (1951)

Set in a diner, this scene finds meaning in a moment most people barely notice. A grandmother and her grandson pause to say grace before eating, their heads bowed amid the clatter and movement of a crowded public space.

What gives Saying Grace its power is not the act itself, but the surrounding reaction. Other diners look on with curiosity, creating an unease between private belief and public life. Rockwell doesn’t exaggerate the moment or moralize it. He simply lets it exist.

The contrast between the sacred and the everyday reflects a recurring theme in Rockwell’s later work: how personal values persist within shared spaces. Faith here isn’t dramatic or defiant. It’s calm, modest and deeply human.

This is one of the most expensive Norman Rockwell paintings ever sold. While the original has already been auctioned for much less than 46 million, you can get your own Saving Grace thanks to all the Norman Rockwell prints out there.

Norman Rockwell Paintings FAQs

How many paintings did Norman Rockwell paint?

Before Rockwell passed away at the age of 84, he solidified his legacy as a prolific artist, producing over 4,000 original pieces in his lifetime. While many artists use their talents as an exploration of the darker corners of the human experience — look no further than Frida Kahlo and Vincent Van Gogh — Norman Rockwell’s paintings often depict sentimentalized portrayals of the human experience.

What Was Norman Rockwell’s Art Style?

There’s a narrative quality to Norman Rockwell paintings that makes them both relatable and engaging. Rockwell’s paintings could be characterized by the American Realism movement, drawing inspiration from the different generations of Americans, both young and old, who made up the daily grind of the time.

His talent for illustration and love for expressive characters gave way to a romanticized view of American life that transcended borders and captured the hearts of the global village.

What are the characteristics of Norman Rockwell's paintings?

Norman Rockwell paintings are highly realistic. You can almost feel the veiny knuckles of an old man’s hand or the soft white and brown fur of a beloved pet. Norman Rockwell paintings have a clear focus, allowing viewers to easily understand his depictions thanks to a lack of visual distractions.

Utilizing a warm and inviting color palette, Rockwell incorporated a sense of whimsy in many of his paintings. Depending on the decade, Rockwell's paintings usually have a patriotic, humorous, nostalgic or politically-geared subject matter. Tired Salesgirl on Christmas Eve, for example, is a social commentary on consumerism during what is meant to be a time of giving, family and love.

How long did it take Norman Rockwell to finish a painting?

According to an article shared by the Brooklyn Museum, Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera, while the artist was a natural storyteller, “he found it difficult to paint purely from imagination.”

And so, by the mid-1930s, photography became an important element to his creative process, which in turn lengthened it as well. From conceptualizing and planning to drawing and revisions, it took Rockwell approximately six to eight weeks to finish a piece.

What is the most valuable Norman Rockwell painting?

What is the most valuable Norman Rockwell painting? Well, it’s hard to pin down the true value of Norman Rockwell’s paintings, but if we were to measure their worth by price, Saving Grace (1951) (number 17 in our list) takes the cake.

According to a report by NPR, this Norman Rockwell painting sold at an auction for $46 million dollars in 2013. At the time, that was the highest price a painting had sold at auction.

It's not quite in the hundreds of millions that the most expensive paintings sell for, but it's pretty high for someone who was considered an illustrator over purely an artist.

Where is the Norman Rockwell Museum?

If you're wondering, "Where can I see Norman Rockwell Paintings?" you will find the largest collection of Norman Rockwell paintings at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

Included in this iconic collection are many of the covers he produced for The Saturday Evening Post. Not only can you explore a plethora of Norman Rockwell paintings, but you can also attend educational programs and events that celebrate Rockwell’s mighty career. You can even visit the gift shop to bring home some Norman Rockwell prints.

Norman Rockwell paintings offer more than technical skill to study. They show how observation, empathy and storytelling can carry just as much weight as composition or brushwork.

Whether you’re interested in how to start oil painting, illustration or simply understanding how art reflects the culture around it, Rockwell’s work reminds us that everyday moments can hold lasting meaning. Studying his paintings isn’t just about learning how he painted, but about seeing how closely art can follow the lives and values of its time.

For even more fun painting ideas, check out other experiences happening on Classpop!